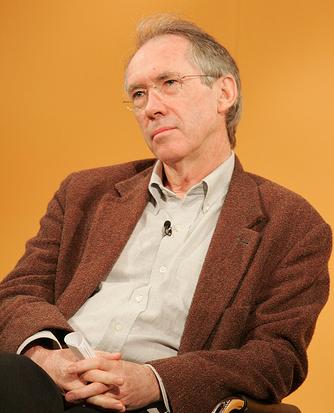

Ian McEwan Frases famosas

Ian McEwan: Frases em inglês

“Let the guilty bury the innocent, and let no one change the evidence”

Fonte: Atonement

“How easily this unthinking family love was forgotten.”

Fonte: Atonement

from The Root of All Evil?, Channel 4 documentary, United Kingdom (January 2006).

“Nations are never virtuous, though they might sometimes think they are.”

Page 149. (A line from Michael Beard's speech at the Savoy Hotel, London.)

Solar (2010)

“I did not kill my father, but I sometimes felt I had helped him on his way.”

Page 9. (Opening line of the book)

The Cement Garden (1978)

From "Faith and Doubt At Ground Zero," Frontline, February, 2002

Fonte: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/faith/interviews/mcewan.html

Page 139. (From the seventh and final short story, 'Psychopolis')

In Between the Sheets (1978)