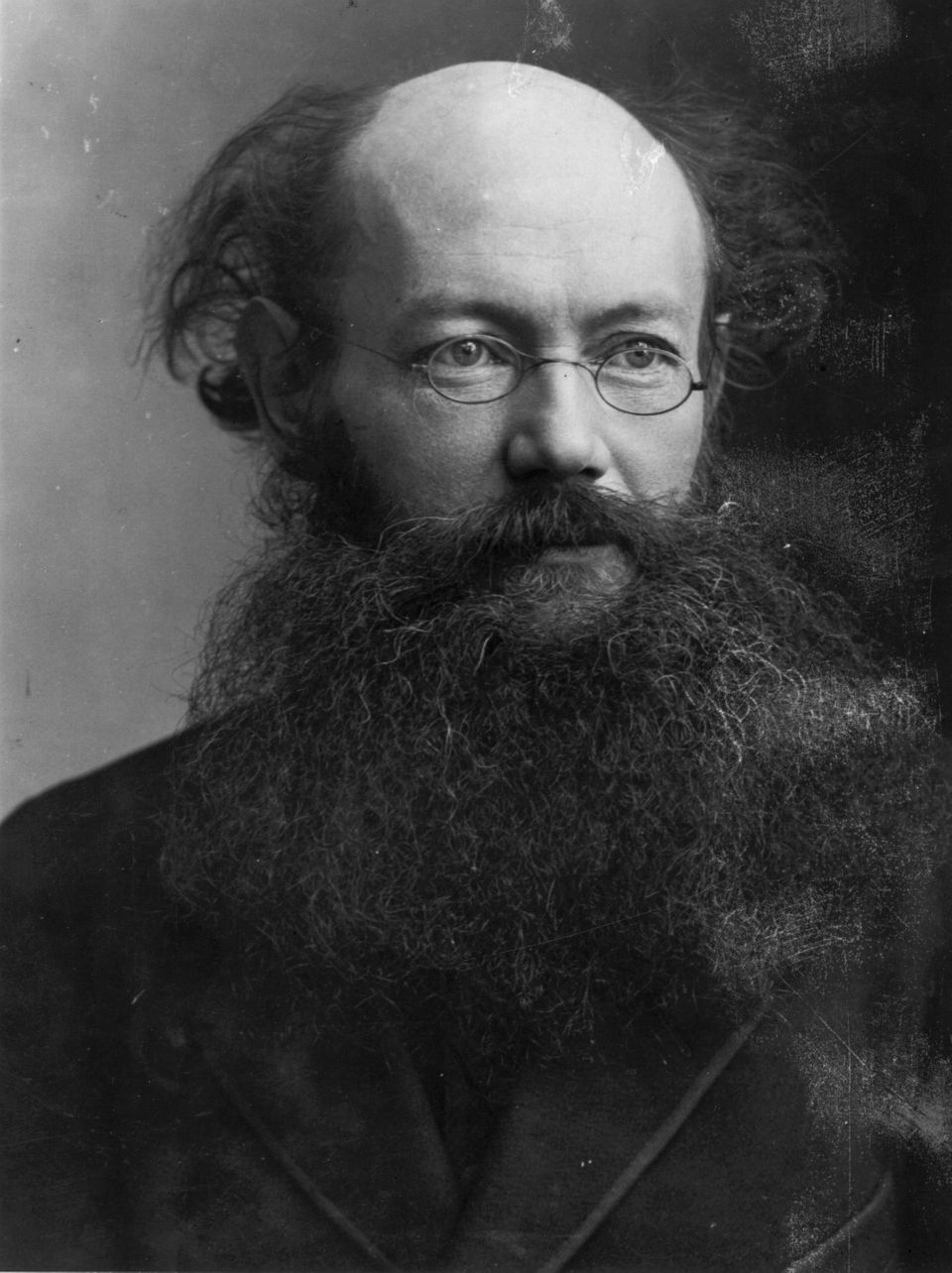

Piotr Kropotkin Frases famosas

carta a um amigo (novembro de 1920), conforme citado em "Peter Kropotkin: From Prince to Rebel" (1990) de George Woodcock e Ivan Avakumovic, p. 428

“Há períodos na vida da sociedade humana quando a revolução torna-se uma necessidade imperativa”

The Spirit of Revolt http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/Anarchist_Archives/kropotkin/spiritofrevolt.html (1880)

Piotr Kropotkin: Frases em inglês

The Spirit of Revolt (1880)

Contexto: One courageous act has sufficed to upset in a few days the entire governmental machinery, to make the colossus tremble; another revolt has stirred a whole province into turmoil, and the army, till now always so imposing, has retreated before a handful of peasants armed with sticks and stones. The people observe that the monster is not so terrible as they thought they begin dimly to perceive that a few energetic efforts will be sufficient to throw it down. Hope is born in their hearts, and let us remember that if exasperation often drives men to revolt, it is always hope, the hope of victory, which makes revolutions.

The government resists; it is savage in its repressions. But, though formerly persecution killed the energy of the oppressed, now, in periods of excitement, it produces the opposite result. It provokes new acts of revolt, individual and collective, it drives the rebels to heroism; and in rapid succession these acts spread, become general, develop. The revolutionary party is strengthened by elements which up to this time were hostile or indifferent to it.

Fonte: Law and Authority (1886), II

Contexto: Legislators confounded in one code the two currents of custom of which we have just been speaking, the maxims which represent principles of morality and social union wrought out as a result of life in common, and the mandates which are meant to ensure external existence to inequality.

Customs, absolutely essential to the very being of society, are, in the code, cleverly intermingled with usages imposed by the ruling caste, and both claim equal respect from the crowd. "Do not kill," says the code, and hastens to add, "And pay tithes to the priest." "Do not steal," says the code, and immediately after, "He who refuses to pay taxes, shall have his hand struck off."

Such was law; and it has maintained its two-fold character to this day. Its origin is the desire of the ruling class to give permanence to customs imposed by themselves for their own advantage. Its character is the skillful commingling of customs useful to society, customs which have no need of law to insure respect, with other customs useful only to rulers, injurious to the mass of the people, and maintained only by the fear of punishment.

Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal (1896)

Contexto: Far be it from us not to recognize the importance of the second factor, moral teaching — especially that which is unconsciously transmitted in society and results from the whole of the ideas and comments emitted by each of us on facts and events of every-day life. But this force can only act on society under one condition, that of not being crossed by a mass of contradictory immoral teachings resulting from the practice of institutions.

In that case its influence is nil or baneful. Take Christian morality: what other teaching could have had more hold on minds than that spoken in the name of a crucified God, and could have acted with all its mystical force, all its poetry of martyrdom, its grandeur in forgiving executioners? And yet the institution was more powerful than the religion: soon Christianity — a revolt against imperial Rome — was conquered by that same Rome; it accepted its maxims, customs, and language. The Christian church accepted the Roman law as its own, and as such — allied to the State — it became in history the most furious enemy of all semi-communist institutions, to which Christianity appealed at Its origin.

Fonte: The State — Its Historic Role (1897), I

Contexto: The Roman Empire was a State in the real sense of the word. To this day it remains the legist's ideal. Its organs covered a vast domain with a tight network. Everything gravitated towards Rome: economic and military life, wealth, education, nay, even religion. From Rome came the laws, the magistrates, the legions to defend the territory, the prefects and the gods, The whole life of the Empire went back to the Senate — later to the Caesar, the all powerful, omniscient, god of the Empire. Every province, every district had its Capitol in miniature, its small portion of Roman sovereignty to govern every aspect of daily life. A single law, that imposed by Rome, dominated that Empire which did not represent a confederation of fellow citizens but was simply a herd of subjects.

Even now, the legist and the authoritarian still admire the unity of that Empire, the unitarian spirit of its laws and, as they put it, the beauty and harmony of that organization.

But the disintegration from within, hastened by the barbarian invasion; the extinction of local life, which could no longer resist the attacks from outside on the one hand nor the canker spreading from the centre on the other; the domination by the rich who had appropriated the land to themselves and the misery of those who cultivated it — all these causes reduced the Empire to a shambles, and on these ruins a new civilization developed which is now ours.

The Spirit of Revolt (1880)

Contexto: The need for a new life becomes apparent. The code of established morality, that which governs the greater number of people in their daily life, no longer seems sufficient. What formerly seemed just is now felt to be a crying injustice. The morality of yesterday is today recognized as revolting immorality. The conflict between new ideas and old traditions flames up in every class of society, in every possible environment, in the very bosom of the family. … Those who long for the triumph of justice, those who would put new ideas into practice, are soon forced to recognize that the realization of their generous, humanitarian and regenerating ideas cannot take place in a society thus constituted; they perceive the necessity of a revolutionary whirlwind which will sweep away all this rottenness, revive sluggish hearts with its breath, and bring to mankind that spirit of devotion, self-denial, and heroism, without which society sinks through degradation and vileness into complete disintegration.

Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal (1896)

Contexto: These societies already begin to encroach everywhere on the functions of the State, and strive to substitute free action of volunteers for that of a centralized State. In England we see arise insurance companies against theft; societies for coast defense, volunteer societies for land defense, which the State endeavors to get under its thumb, thereby making them instruments of domination, although their original aim was to do without the State. Were it not for Church and State, free societies would have already conquered the whole of the immense domain of education. And, in spite of all difficulties, they begin to invade this domain as well, and make their influence already felt.

And when we mark the progress already accomplished in that direction, in spite of and against the State, which tries by all means to maintain its supremacy of recent origin; when we see how voluntary societies invade everything and are only impeded in their development by the State, we are forced to recognize a powerful tendency, a latent force in modern society.

Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902)

Contexto: In primitive Buddhism, in primitive Christianity, in the writings of some of the Mussulman teachers, in the early movements of the Reform, and especially in the ethical and philosophical movements of the last century and of our own times, the total abandonment of the idea of revenge, or of "due reward" — of good for good and evil for evil — is affirmed more and more vigorously. The higher conception of "no revenge for wrongs," and of freely giving more than one expects to receive from his neighbours, is proclaimed as being the real principle of morality — a principle superior to mere equivalence, equity, or justice, and more conducive to happiness. And man is appealed to to be guided in his acts, not merely by love, which is always personal, or at the best tribal, but by the perception of his oneness with each human being. In the practice of mutual aid, which we can retrace to the earliest beginnings of evolution, we thus find the positive and undoubted origin of our ethical conceptions; and we can affirm that in the ethical progress of man, mutual support — not mutual struggle — has had the leading part. In its wide extension, even at the present time, we also see the best guarantee of a still loftier evolution of our race.

Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902)

Contexto: As to the sudden industrial progress which has been achieved during our own century, and which is usually ascribed to the triumph of individualism and competition, it certainly has a much deeper origin than that. Once the great discoveries of the fifteenth century were made, especially that of the pressure of the atmosphere, supported by a series of advances in natural philosophy — and they were made under the medieval city organization, — once these discoveries were made, the invention of the steam-motor, and all the revolution which the conquest of a new power implied, had necessarily to follow... To attribute, therefore, the industrial progress of our century to the war of each against all which it has proclaimed, is to reason like the man who, knowing not the causes of rain, attributes it to the victim he has immolated before his clay idol. For industrial progress, as for each other conquest over nature, mutual aid and close intercourse certainly are, as they have been, much more advantageous than mutual struggle.

The Spirit of Revolt (1880)

Contexto: One courageous act has sufficed to upset in a few days the entire governmental machinery, to make the colossus tremble; another revolt has stirred a whole province into turmoil, and the army, till now always so imposing, has retreated before a handful of peasants armed with sticks and stones. The people observe that the monster is not so terrible as they thought they begin dimly to perceive that a few energetic efforts will be sufficient to throw it down. Hope is born in their hearts, and let us remember that if exasperation often drives men to revolt, it is always hope, the hope of victory, which makes revolutions.

The government resists; it is savage in its repressions. But, though formerly persecution killed the energy of the oppressed, now, in periods of excitement, it produces the opposite result. It provokes new acts of revolt, individual and collective, it drives the rebels to heroism; and in rapid succession these acts spread, become general, develop. The revolutionary party is strengthened by elements which up to this time were hostile or indifferent to it.

The Spirit of Revolt (1880)

Contexto: In periods of frenzied haste toward wealth, of feverish speculation and of crisis, of the sudden downfall of great industries and the ephemeral expansion of other branches of production, of scandalous fortunes amassed in a few years and dissipated as quickly, it becomes evident that the economic institutions which control production and exchange are far from giving to society the prosperity which they are supposed to guarantee; they produce precisely the opposite result. … Human society is seen to be splitting more and more into two hostile camps, and at the same time to be subdividing into thousands of small groups waging merciless war against each other. Weary of these wars, weary of the miseries which they cause, society rushes to seek a new organization; it clamors loudly for a complete remodeling of the system of property ownership, of production, of exchange and all economic relations which spring from it.

"Anarchism" article in Encyclopedia Britannica (1910) "The Historical Development of Anarchism", as quoted in Anarchism: A Collection of Revolutionary Writings (1927), p. 288

Contexto: The best exponent of anarchist philosophy in ancient Greece was Zeno (342-267 or 270 B. C.), from Crete, the founder of the Stoic philosophy, who distinctly opposed his conception of a free community without government to the state-Utopia of Plato. He repudiated the omnipotence of the State, its intervention and regimentation, and proclaimed the sovereignty of the moral law of the individual — remarking already that, while the necessary instinct of self-preservation leads man to egotism, nature has supplied a corrective to it by providing man with another instinct — that of sociability. When men are reasonable enough to follow their natural instincts, they will unite across the frontiers and constitute the Cosmos. They will have no need of law-courts or police, will have no temples and no public worship, and use no money — free gifts taking the place of the exchanges. Unfortunately, the writings of Zeno have not reached us and are only known through fragmentary quotations. However, the fact that his very wording is similar to the wording now in use, shows how deeply is laid the tendency of human nature of which he was the mouthpiece.

The Conquest of Bread (1907), p. 14 http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/anarchist_archives/kropotkin/conquest/toc.html

Variant: All things for all men, since all men have need of them, since all men worked to produce them in the measure of their strength, and since it is not possible to evaluate everyone's part in the production of the world's wealth... All is for all!

This variant was probably produced by a combination of accidental as well as deliberate omission, rather than a separate translation.

Contexto: The means of production being the collective work of humanity, the product should be the collective property of the race. Individual appropriation is neither just nor serviceable. All belongs to all. All things are for all men, since all men have need of them, since all men have worked in the measure of their strength to produce them, and since it is not possible to evaluate every one's part in the production of the world's wealth.

All things are for all. Here is an immense stock of tools and implements; here are all those iron slaves which we call machines, which saw and plane, spin and weave for us, unmaking and remaking, working up raw matter to produce the marvels of our time. But nobody has the right to seize a single one of these machines and say, "This is mine; if you want to use it you must pay me a tax on each of your products," any more than the feudal lord of medieval times had the right to say to the peasant, "This hill, this meadow belong to me, and you must pay me a tax on every sheaf of corn you reap, on every rick you build."

All is for all! If the man and the woman bear their fair share of work, they have a right to their fair share of all that is produced by all, and that share is enough to secure them well-being. No more of such vague formulas as "The Right to work," or "To each the whole result of his labour." What we proclaim is The Right to Well-Being: Well-Being for All!

The Spirit of Revolt (1880)

Contexto: Whoever has a slight knowledge of history and a fairly clear head knows perfectly well from the beginning that theoretical propaganda for revolution will necessarily express itself in action long before the theoreticians have decided that the moment to act has come. Nevertheless, the cautious theoreticians are angry at these madmen, they excommunicate them, they anathematize them. But the madmen win sympathy, the mass of the people secretly applaud their courage, and they find imitators. In proportion as the pioneers go to fill the jails and the penal colonies, others continue their work; acts of illegal protest, of revolt, of vengeance, multiply.

Indifference from this point on is impossible. Those who at the beginning never so much as asked what the "madmen" wanted, are compelled to think about them, to discuss their ideas, to take sides for or against. By actions which compel general attention, the new idea seeps into people's minds and wins converts. One such act may, in a few days, make more propaganda than thousands of pamphlets.

Above all, it awakens the spirit of revolt: it breeds daring. The old order, supported by the police, the magistrates, the gendarmes and the soldiers, appeared unshakable, like the old fortress of the Bastille, which also appeared impregnable to the eyes of the unarmed people gathered beneath its high walls equipped with loaded cannon. But soon it became apparent that the established order has not the force one had supposed.

“The best exponent of anarchist philosophy in ancient Greece was Zeno”

"Anarchism" article in Encyclopedia Britannica (1910) "The Historical Development of Anarchism", as quoted in Anarchism: A Collection of Revolutionary Writings (1927), p. 288

Contexto: The best exponent of anarchist philosophy in ancient Greece was Zeno (342-267 or 270 B. C.), from Crete, the founder of the Stoic philosophy, who distinctly opposed his conception of a free community without government to the state-Utopia of Plato. He repudiated the omnipotence of the State, its intervention and regimentation, and proclaimed the sovereignty of the moral law of the individual — remarking already that, while the necessary instinct of self-preservation leads man to egotism, nature has supplied a corrective to it by providing man with another instinct — that of sociability. When men are reasonable enough to follow their natural instincts, they will unite across the frontiers and constitute the Cosmos. They will have no need of law-courts or police, will have no temples and no public worship, and use no money — free gifts taking the place of the exchanges. Unfortunately, the writings of Zeno have not reached us and are only known through fragmentary quotations. However, the fact that his very wording is similar to the wording now in use, shows how deeply is laid the tendency of human nature of which he was the mouthpiece.

An Appeal to the Young (1880)

Contexto: If you reason instead of repeating what is taught you; if you analyze the law and strip off those cloudy fictions with which it has been draped in order to conceal its real origin, which is the right of the stronger, and its substance, which has ever been the consecration of all the tyrannies handed down to mankind through its long and bloody history; when you have comprehended this, your contempt for the law will be profound indeed. You will understand that to remain the servant of the written law is to place yourself every day in opposition to the law of conscience, and to make a bargain on the wrong side; and, since this struggle cannot go on forever, you will either silence your conscience and become a scoundrel, or you will break with tradition, and you will work with us for the utter destruction of all this injustice, economic, social and political.

“Such was law; and it has maintained its two-fold character to this day.”

Fonte: Law and Authority (1886), II

Contexto: Legislators confounded in one code the two currents of custom of which we have just been speaking, the maxims which represent principles of morality and social union wrought out as a result of life in common, and the mandates which are meant to ensure external existence to inequality.

Customs, absolutely essential to the very being of society, are, in the code, cleverly intermingled with usages imposed by the ruling caste, and both claim equal respect from the crowd. "Do not kill," says the code, and hastens to add, "And pay tithes to the priest." "Do not steal," says the code, and immediately after, "He who refuses to pay taxes, shall have his hand struck off."

Such was law; and it has maintained its two-fold character to this day. Its origin is the desire of the ruling class to give permanence to customs imposed by themselves for their own advantage. Its character is the skillful commingling of customs useful to society, customs which have no need of law to insure respect, with other customs useful only to rulers, injurious to the mass of the people, and maintained only by the fear of punishment.

Fonte: Law and Authority (1886), II

Contexto: Relatively speaking, law is a product of modern times. For ages and ages mankind lived without any written law, even that graved in symbols upon the entrance stones of a temple. During that period, human relations were simply regulated by customs, habits, and usages, made sacred by constant repetition, and acquired by each person in childhood, exactly as he learned how to obtain his food by hunting, cattle-rearing, or agriculture.

All human societies have passed through this primitive phase, and to this day a large proportion of mankind have no written law. Every tribe has its own manners and customs; customary law, as the jurists say. It has social habits, and that suffices to maintain cordial relations between the inhabitants of the village, the members of the tribe or community. Even amongst ourselves — the "civilized" nations — when we leave large towns, and go into the country, we see that there the mutual relations of the inhabitants are still regulated according to ancient and generally accepted customs, and not according to the written law of the legislators.

Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal (1896)

Contexto: Take any work on astronomy of the last century, or the beginning of ours. You will no longer find in it, it goes without saying, our tiny planet placed in the center of the universe. But you will meet at every step the idea of a central luminary — the sun — which by its powerful attraction governs our planetary world. From this central body radiates a force guiding the course of the planets, and maintaining the harmony of the system. Issued from a central agglomeration, planets have, so to say, budded from it; they owe their birth to this agglomeration; they owe everything to the radiant star that represents it still: the rhythm of their movements, their orbits set at wisely regulated distances, the life that animates them and adorns their surfaces. And when any perturbation disturbs their course and makes them deviate from their orbits, the central body re-establishes order in the system; it assures and perpetuates its existence.

This conception, however, is also disappearing as the other one did. After having fixed all their attention on the sun and the large planets, astronomers are beginning to study now the infinitely small ones that people the universe. And they discover that the interplanetary and interstellar spaces are peopled and crossed in all imaginable directions by little swarms of matter, invisible, infinitely small when taken separately, but all-powerful in their numbers.

Fonte: Law and Authority (1886), II

Contexto: Legislators confounded in one code the two currents of custom of which we have just been speaking, the maxims which represent principles of morality and social union wrought out as a result of life in common, and the mandates which are meant to ensure external existence to inequality.

Customs, absolutely essential to the very being of society, are, in the code, cleverly intermingled with usages imposed by the ruling caste, and both claim equal respect from the crowd. "Do not kill," says the code, and hastens to add, "And pay tithes to the priest." "Do not steal," says the code, and immediately after, "He who refuses to pay taxes, shall have his hand struck off."

Such was law; and it has maintained its two-fold character to this day. Its origin is the desire of the ruling class to give permanence to customs imposed by themselves for their own advantage. Its character is the skillful commingling of customs useful to society, customs which have no need of law to insure respect, with other customs useful only to rulers, injurious to the mass of the people, and maintained only by the fear of punishment.

Letter to Vladimir Lenin (21 December 1920); as quoted in Peter Kropotkin : From Prince to Rebel (1990) by George Woodcock and Ivan Avakumovic, p. 426

Variant translation: Whoever holds dear the future of communism cannot embark upon such measures.

It is possible that no one has explained what a hostage really is? A hostage is imprisoned not as punishment for some crime. He is held in order to blackmail the enemy with his death.

As translated in Selected Writings on Anarchism and Revolution (1970) edited and translated by Martin A. Miller http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/anarchist_Archives/kropotkin/kropotlenindec20.html

Contexto: Vladimir Ilyich, your concrete actions are completely unworthy of the ideas you pretend to hold.

Is it possible that you do not know what a hostage really is — a man imprisoned not because of a crime he has committed, but only because it suits his enemies to exert blackmail on his companions? … If you admit such methods, one can foresee that one day you will use torture, as was done in the Middle Ages.

I hope you will not answer me that Power is for political men a professional duty, and that any attack against that power must be considered as a threat against which one must guard oneself at any price. This opinion is no longer held even by kings... Are you so blinded, so much a prisoner of your own authoritarian ideas, that you do not realise that being at the head of European Communism, you have no right to soil the ideas which you defend by shameful methods … What future lies in store for Communism when one of its most important defenders tramples in this way every honest feeling?

Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal (1896)

Contexto: It is not without a certain hesitation that I have decided to take the philosophy and ideal of Anarchy as the subject of this lecture.

Those who are persuaded that Anarchy is a collection of visions relating to the future, and an unconscious striving toward the destruction of all present civilization, are still very numerous; and to clear the ground of such prejudices of our education as maintain this view we should have, perhaps, to enter into many details which it would be difficult to embody in a single lecture. Did not the Parisian press, only two or three years ago, maintain that the whole philosophy of Anarchy consisted in destruction, and that its only argument was violence?

Nevertheless Anarchists have been spoken of so much lately, that part of the public has at last taken to reading and discussing our doctrines. Sometimes men have even given themselves trouble to reflect, and at the present moment we have at least gained a point: it is willingly admitted that Anarchists have an ideal. Their ideal is even found too beautiful, too lofty for a society not composed of superior beings.

“The unsociable species, on the contrary, are doomed to decay.”

Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902)

Contexto: In the animal world we have seen that the vast majority of species live in societies, and that they find in association the best arms for the struggle for life: understood, of course, in its wide Darwinian sense — not as a struggle for the sheer means of existence, but as a struggle against all natural conditions unfavourable to the species. The animal species, in which individual struggle has been reduced to its narrowest limits, and the practice of mutual aid has attained the greatest development, are invariably the most numerous, the most prosperous, and the most open to further progress. The mutual protection which is obtained in this case, the possibility of attaining old age and of accumulating experience, the higher intellectual development, and the further growth of sociable habits, secure the maintenance of the species, its extension, and its further progressive evolution. The unsociable species, on the contrary, are doomed to decay.

Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902)

Contexto: In the animal world we have seen that the vast majority of species live in societies, and that they find in association the best arms for the struggle for life: understood, of course, in its wide Darwinian sense — not as a struggle for the sheer means of existence, but as a struggle against all natural conditions unfavourable to the species. The animal species, in which individual struggle has been reduced to its narrowest limits, and the practice of mutual aid has attained the greatest development, are invariably the most numerous, the most prosperous, and the most open to further progress. The mutual protection which is obtained in this case, the possibility of attaining old age and of accumulating experience, the higher intellectual development, and the further growth of sociable habits, secure the maintenance of the species, its extension, and its further progressive evolution. The unsociable species, on the contrary, are doomed to decay.

The Spirit of Revolt (1880)

Contexto: How is it that men who only yesterday were complaining quietly of their lot as they smoked their pipes, and the next moment were humbly saluting the local guard and gendarme whom they had just been abusing, — how is it that these same men a few days later were capable of seizing their scythes and their iron-shod pikes and attacking in his castle the lord who only yesterday was so formidable? By what miracle were these men, whose wives justly called them cowards, transformed in a day into heroes, marching through bullets and cannon balls to the conquest of their rights? How was it that words, so often spoken and lost in the air like the empty chiming of bells, were changed into actions?

The answer is easy.

Action, the continuous action, ceaselessly renewed, of minorities brings about this transformation. Courage, devotion, the spirit of sacrifice, are as contagious as cowardice, submission, and panic.

What forms will this action take? All forms, — indeed, the most varied forms, dictated by circumstances, temperament, and the means at disposal. Sometimes tragic, sometimes humorous, but always daring; sometimes collective, sometimes purely individual, this policy of action will neglect none of the means at hand, no event of public life, in order to keep the spirit alive, to propagate and find expression for dissatisfaction, to excite hatred against exploiters, to ridicule the government and expose its weakness, and above all and always, by actual example, to awaken courage and fan the spirit of revolt.

Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal (1896)

Contexto: If every Socialist will carry his thoughts back to an earlier date, he will no doubt remember the host of prejudices aroused in him when, for the first time, he came to the idea that abolishing the capitalist system and private appropriation of land and capital had become an historical necessity.

The same feelings are today produced in the man who for the first time hears that the abolition of the State, its laws, its entire system of management, governmentalism and centralization, also becomes an historical necessity: that the abolition of the one without the abolition of the other is materially impossible. Our whole education — made, be it noted, by Church and State, in the interests of both — revolts at this conception.

Is it less true for that? And shall we allow our belief in the State to survive the host of prejudices we have already sacrificed for our emancipation?

“Idlers do not make history: they suffer it!”

Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal (1896)

Contexto: All is linked, all holds together under the present economic system, and all tends to make the fall of the industrial and mercantile system under which we live inevitable. Its duration is but a question of time that may already be counted by years and no longer by centuries. A question of time — and energetic attack on our part! Idlers do not make history: they suffer it!

Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal (1896)

Contexto: Once a German jurist of great renown, Ihering, wanted to sum up the scientific work of his life and write a treatise, in which he proposed to analyze the factors that preserve social life in society. "Purpose in Law" (Der Zweck im Rechte), such is the title of that book, which enjoys a well-deserved reputation.

He made an elaborate plan of his treatise, and, with much erudition, discussed both coercive factors which are used to maintain society: wagedom and the different forms of coercion which are sanctioned by law. At the end of his work he reserved two paragraphs only to mention the two non-coercive factors — the feeling of duty and the feeling of mutual sympathy — to which he attached little importance, as might be expected from a writer in law.

But what happened? As he went on analyzing the coercive factors he realized their insufficiency. He consecrated a whole volume to their analysis, and the result was to lessen their importance! When he began the last two paragraphs, when he began to reflect upon the non-coercive factors of society, he perceived, on the contrary, their immense, outweighing importance; and instead of two paragraphs, he found himself obliged to write a second volume, twice as large as the first, on these two factors: voluntary restraint and mutual help; and yet, he analyzed but an infinitesimal part of these latter — those which result from personal sympathy — and hardly touched free agreement, which results from social institutions.

Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal (1896)

Contexto: It is often said that Anarchists live in a world of dreams to come, and do not see the things which happen today. We do see them only too well, and in their true colors, and that is what makes us carry the hatchet into the forest of prejudice that besets us.

Far from living in a world of visions and imagining men better than they are, we see them as they are; and that is why we affirm that the best of men is made essentially bad by the exercise of authority, and that the theory of the "balancing of powers" and "control of authorities" is a hypocritical formula, invented by those who have seized power, to make the "sovereign people," whom they despise, believe that the people themselves are governing. It is because we know men that we say to those who imagine that men would devour one another without those governors: "You reason like the king, who, being sent across the frontier, called out, 'What will become of my poor subjects without me?'"

Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal (1896)

Contexto: Oh, the beautiful utopia, the lovely Christmas dream we can make as soon as we admit that those who govern represent a superior caste, and have hardly any or no knowledge of simple mortals' weaknesses! It would then suffice to make them control one another in hierarchical fashion, to let them exchange fifty papers, at most, among different administrators, when the wind blows down a tree on the national road. Or, if need be, they would have only to be valued at their proper worth, during elections, by those same masses of mortals which are supposed to be endowed with all stupidity in their mutual relations but become wisdom itself when they have to elect their masters.

All the science of government, imagined by those who govern, is imbibed with these utopias. But we know men too well to dream such dreams. We have not two measures for the virtues of the governed and those of the governors; we know that we ourselves are not without faults and that the best of us would soon be corrupted by the exercise of power. We take men for what they are worth — and that is why we hate the government of man by man, and that we work with all our might — perhaps not strong enough — to put an end to it.

But it is not enough to destroy. We must also know how to build, and it is owing to not having thought about it that the masses have always been led astray in all their revolutions. After having demolished they abandoned the care of reconstruction to the middle class people, who possessed a more or less precise conception of what they wished to realize, and who consequently reconstituted authority to their own advantage.

That is why Anarchy, when it works to destroy authority in all its aspects, when it demands the abrogation of laws and the abolition of the mechanism that serves to impose them, when it refuses all hierarchical organization and preaches free agreement — at the same time strives to maintain and enlarge the precious kernel of social customs without which no human or animal society can exist. Only, instead of demanding that those social customs should be maintained through the authority of a few, it demands it from the continued action of all.

Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal (1896)

Contexto: Once a German jurist of great renown, Ihering, wanted to sum up the scientific work of his life and write a treatise, in which he proposed to analyze the factors that preserve social life in society. "Purpose in Law" (Der Zweck im Rechte), such is the title of that book, which enjoys a well-deserved reputation.

He made an elaborate plan of his treatise, and, with much erudition, discussed both coercive factors which are used to maintain society: wagedom and the different forms of coercion which are sanctioned by law. At the end of his work he reserved two paragraphs only to mention the two non-coercive factors — the feeling of duty and the feeling of mutual sympathy — to which he attached little importance, as might be expected from a writer in law.

But what happened? As he went on analyzing the coercive factors he realized their insufficiency. He consecrated a whole volume to their analysis, and the result was to lessen their importance! When he began the last two paragraphs, when he began to reflect upon the non-coercive factors of society, he perceived, on the contrary, their immense, outweighing importance; and instead of two paragraphs, he found himself obliged to write a second volume, twice as large as the first, on these two factors: voluntary restraint and mutual help; and yet, he analyzed but an infinitesimal part of these latter — those which result from personal sympathy — and hardly touched free agreement, which results from social institutions.