“O mundo intriga-me. Não posso imaginar que este relógio exista e não haja relojoeiro.”

Artigo de Richard Dawkins, Tradução: André Díspore Cancian, Fonte: Council for Secular Humanism

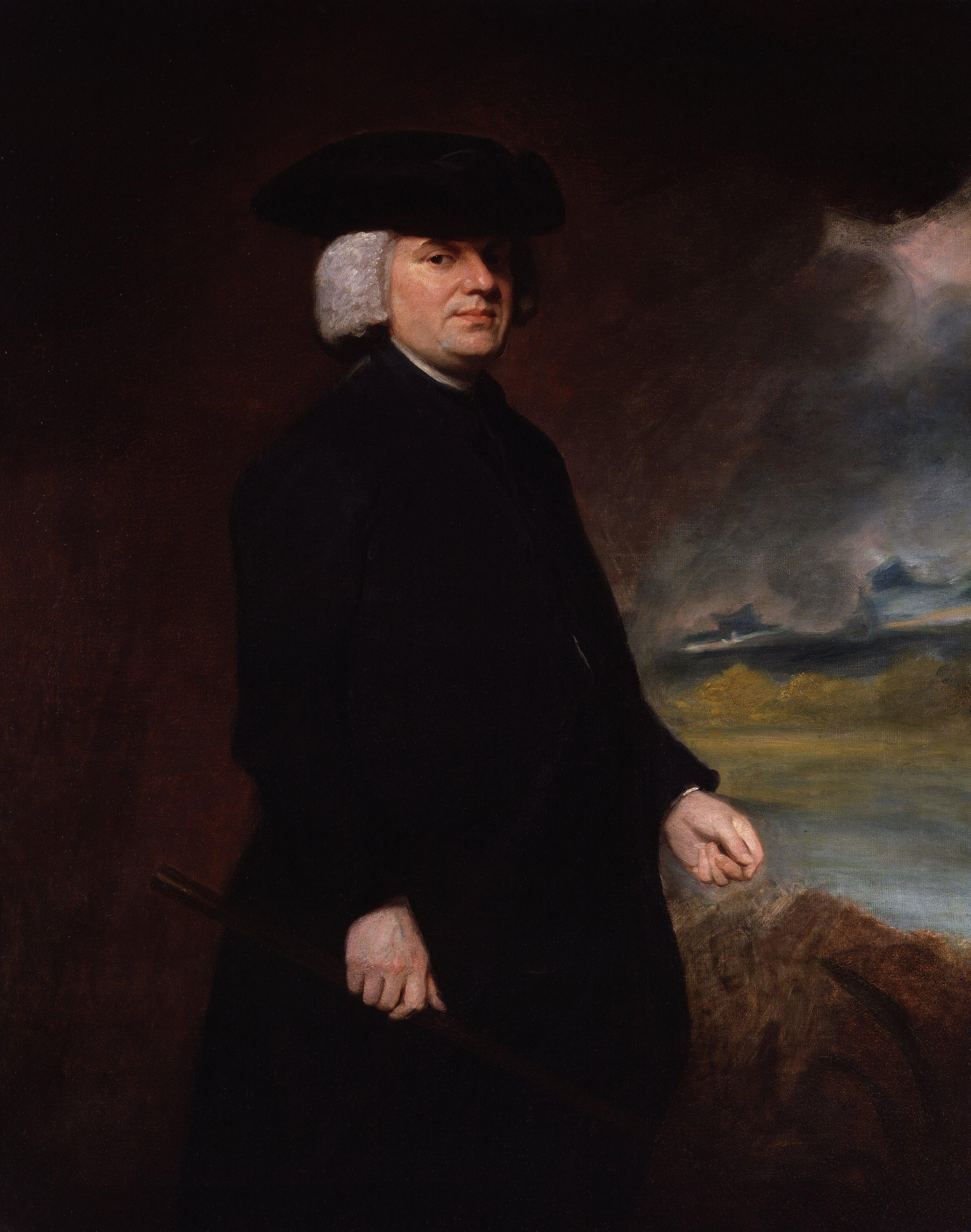

William Paley foi um teólogo e filósofo britânico. Autor da obra Natural Theology, argumentou que a complexidade e adaptações dos seres vivos eram prova da intervenção divina na criação, no que se veio chamar "analogia do relojoeiro". Wikipedia

“O mundo intriga-me. Não posso imaginar que este relógio exista e não haja relojoeiro.”

Artigo de Richard Dawkins, Tradução: André Díspore Cancian, Fonte: Council for Secular Humanism

Fonte: Natural Theology (1802), Ch. 27 : Conclusion.

Contexto: It is a step to have it proved, that there must be something in the world more than what we see. It is a further step to know, that, amongst the invisible things of nature, there must be an intelligent mind, concerned in its production, order, and support. These points being assured to us by Natural Theology, we may well leave to Revelation the disclosure of many particulars, which our researches cannot reach, respecting either the nature of this Being as the original cause of all things, or his character and designs as a moral governor; and not only so, but the more full confirmation of other particulars, of which, though they do not lie altogether beyond our reasonings and our probabilities, the certainty is by no means equal to the importance. The true theist will be the first to listen to any credible communication of Divine knowledge. Nothing which he has learned from Natural Theology, will diminish his desire of further instruction, or his disposition to receive it with humility and thankfulness. He wishes for light: he rejoices in light. His inward veneration of this great Being, will incline him to attend with the utmost seriousness, not only to all that can be discovered concerning him by researches into nature, but to all that is taught by a revelation, which gives reasonable proof of having proceeded from him.

Fonte: Natural Theology (1802), Ch. 1 : State of the Argument.

Contexto: In crossing a heath, suppose I pitched my foot against a stone and were asked how the stone came to be there, I might possibly answer that for anything I knew to the contrary it had lain there forever; nor would it, perhaps, be very easy to show the absurdity of this answer. But suppose I found a watch upon the ground, and it should be inquired how the watch happened to be in that place, I should hardly think of the answer which I had given, that for anything I knew the watch might have always been there. Yet why should not this answer serve for the watch as well as for the stone; why is it not admissible in that second case as in the first? For this reason, and for no other, namely, that when we come to inspect the watch, we perceive — what we could not discover in the stone — that its several parts are framed and put together for a purpose, e. g., that they are so formed and adjusted as to produce motion, and that motion so regulated as to point out the hour of the day; that if the different parts had been differently shaped from what they are, or placed in any other manner or in any other order than that in which they are placed, either no motion at all would have carried on in the machine, or none which would have answered the use that is now served by it.

This mechanism being observed … the inference we think is inevitable, that the watch must have had a maker — that there must have existed, at some time and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers who formed it for the purpose which we find it actually to answer, who comprehended its construction and designed its use.

Nor would it, I apprehend, weaken the conclusion, that we had never seen a watch made; that we had never known an artist capable of making one; that we were altogether incapable of executing such a piece of workmanship ourselves, or of understanding in what manner it was performed; all this being no more than what is true of some exquisite remains of ancient art, of some lost arts, and, to the generality of mankind, of the more curious productions of modern manufacture.

Fonte: Natural Theology (1802), Ch. 24 : Of the Natural Attributes of the Deity.

Fonte: Natural Theology (1802), Ch. 26 : The Goodness of the Deity.

“Wanton, and, what is worse, studied cruelty to brutes, is certainly wrong.”

Vol. I, Book II, Ch. XI.

The Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy (1785)

Fonte: Natural Theology (1802), Ch. 27 : Conclusion.

Fonte: Natural Theology (1802), Ch. 3 : Application of the Argument.

Fonte: Natural Theology (1802), Ch. 26 : The Goodness of the Deity.

Vol. I, Book II, Ch. V.

The Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy (1785)

Natural Theology (1802)

contempt prior to examination.

A View of the Evidences of Christianity (1794).

As quoted or paraphrased in Anglo-Israel or, The British Nation: The Lost Tribes of Israel (1879) by Rev. William H. Poole.

A similar statement apparently derived from this version has become widely attributed to Herbert Spencer, but there are no records of Spencer ever saying or writing it, the first known attributions to him occurring in 1922 as the epigraph to Le Roy Campbell's The True Function of Relaxation in Piano Playing: A Treatise on the Psycho-Physical Aspect of Piano Playing, With Exercises for Acquiring Relaxation: https://books.google.com/books?id=gjMuAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false "There is a principle which is a bar against all information, which is proof against all argument and which cannot fail to keep a man in everlasting ignorance! That principle is condemnation before investigation".

Variante: There is a principle which is a bar against all information, which is proof against all argument, and which cannot fail to keep a man in everlasting ignorance. This principle is, contempt prior to examination.

Fonte: Natural Theology (1802), Ch. 27 : Conclusion.

Vol. I, Book II, Ch. XI.

The Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy (1785)

Vol. II, Book VI, Ch. I.

The Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy (1785)