"Notes on Professor Robison's Dissertation on Steam-engines" (1769)

Contexto: In the winter of 1763-4, having occasion to repair a model of Newcomen's engine belonging to the Natural Philosophy class of the University of Glasgow, my mind was again directed to it. At that period my knowledge was derived principally from Desaguliers, and partly from Belidor. I set about repairing it as a mere mechanician; and when that was done, and it was set to work, I was surprised to find that its boiler could not supply it with steam, though apparently quite large enough... By blowing the fire it was made to take a few strokes, but required an enormous quantity of injection water, though it was very lightly loaded by the column of water in the pump. It soon occurred that this was caused by the little cylinder exposing a greater surface to condense the steam, than the cylinders of larger engines did in proportion to their respective contents. It was found that by shortening the column of water in the pump, the boiler could supply the cylinder with steam, and that the engine would work regularly with a moderate quantity of injection. It now appeared that the cylinder of the model, being of brass, would conduct heat much better than the cast-iron cylinders of larger engines, (generally covered on the inside with a stony crust), and that considerable advantage could be gained by making the cylinders of some substance that would receive and give out heat slowly. Of these, wood seemed to be the most likely, provided it should prove sufficiently durable. A small engine was, therefore, constructed... made of wood, soaked in linseed oil, and baked to dryness. With this engine many experiments were made; but it was soon found that the wooden cylinder was not likely to prove durable, and that the steam condensed in filling it still exceeded the proportion of that required for large engines, according to the statements of Desaguliers. It was also found that all attempts to produce a better exhaustion by throwing in more injection, caused a disproportionate waste of steam. On reflection, the cause of this seemed to be the boiling of water in vacuo at low heats, a discovery lately made by Dr. Cullen and some other philosophers... and consequently at greater heats, the water in the cylinder would, produce a steam which would in part resist the pressure of the atmosphere.

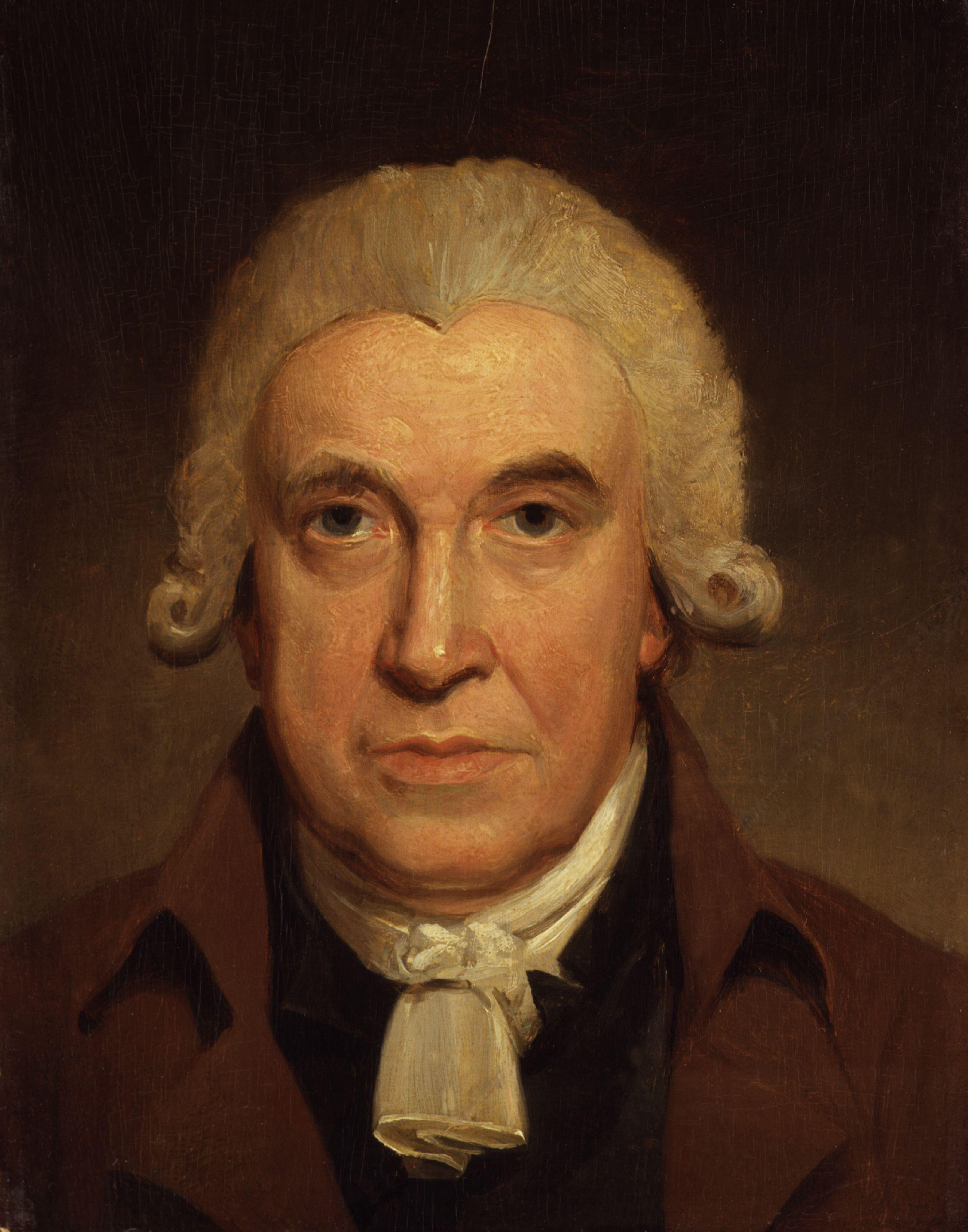

James Watt: Frases em inglês

Attributed to James Watt in: Joel Mokyr, The lever of riches: Technological creativity and economic progress. Oxford University Press, 1992. p, 245

"Notes on Professor Robison's Dissertation on Steam-engines" (1769)

Contexto: In Newcomen's engine, the piston is kept tight by water, which could not be applicable in this new method; as, if any of it entered into a partially-exhausted and hot cylinder, it would boil, and prevent the production of a vacuum, and would also cool the cylinder by its evaporation during the descent of the piston. I proposed to remedy this defect by employing wax, tallow, or other grease, to lubricate and keep the piston tight. It next occurred to me, that the mouth of the cylinder being open, the air which entered to act on the piston would cool the cylinder, and condense some steam on again filling it. I therefore proposed to put an air-tight cover upon the cylinder, with a hole and stuffing-box for the piston-rod to slide through, and to admit steam above the piston to act upon it, instead of the atmosphere.... There still remained another source of the destruction of steam, the cooling of the cylinder by the external air, which would produce an internal condensation whenever steam entered it, and which would be repeated every stroke; this I proposed to remedy by an external cylinder, containing steam, surrounded by another of wood, or of some other substance which would conduct heat slowly.

"Notes on Professor Robison's Dissertation on Steam-engines" (1769)

“In Newcomen's engine, the piston is kept tight by water”

"Notes on Professor Robison's Dissertation on Steam-engines" (1769)

Contexto: In Newcomen's engine, the piston is kept tight by water, which could not be applicable in this new method; as, if any of it entered into a partially-exhausted and hot cylinder, it would boil, and prevent the production of a vacuum, and would also cool the cylinder by its evaporation during the descent of the piston. I proposed to remedy this defect by employing wax, tallow, or other grease, to lubricate and keep the piston tight. It next occurred to me, that the mouth of the cylinder being open, the air which entered to act on the piston would cool the cylinder, and condense some steam on again filling it. I therefore proposed to put an air-tight cover upon the cylinder, with a hole and stuffing-box for the piston-rod to slide through, and to admit steam above the piston to act upon it, instead of the atmosphere.... There still remained another source of the destruction of steam, the cooling of the cylinder by the external air, which would produce an internal condensation whenever steam entered it, and which would be repeated every stroke; this I proposed to remedy by an external cylinder, containing steam, surrounded by another of wood, or of some other substance which would conduct heat slowly.

"Notes on Professor Robison's Dissertation on Steam-engines" (1769)